A Matter of Proportion

By Fred Lanting SV Judge

Many thanks to Mr. Lanting for allowing me to

place this excellent article on my website

Proportions, Function, and Breed Standards: Leg-length Ratios,

Using the Vizsla and the German Shepherd Dog as Examples

by Fred Lanting

As of early 2003, there is still an argument in the circles of Vizsla fanciers in the Vizsla Club of America, VCA, about body proportions and the wording of the Standard. This Hungarian breed of dog is an agile hunter of moderate size, well suited to “upland” fieldwork (woods, broken fields, pastures). There are some who want the Standard reworded to aim at a dog with exactly as much depth of chest as “daylight” under the torso, and opponents who insist on retaining the ideal of slightly more proportion of height being underneath the chest (although they use the elbow as a reference instead). A similar, though more extreme, difference of opinion exists among American GSD breeders, by the way, and we'll look at that in more detail after we consider the Vizsla.

For comparison right now, though, it should be said that the Breed Standard of the SV (Club for GSDs, HQ'd in Germany) says: “The depth of chest should be about 45 % to 48 % of the dog's height at the withers.” This is approximately the right proportion for almost any dog of medium-to-large size and normal anatomy (i.e., excluding dwarf, toy, and giant breeds) that is similar to the ancestral type. If one aims for about 55% of the dog's height being below the elbow and the chest underline there, it will be as ideal as possible. The withers height as measured (immediately behind the shoulder blade) and the “stick” resting on the vertebrae there, allows the vertical portion of the wicket to pass along or immediately behind the “point” of the elbow (olecranon process), and the horizontal foot of the device to be on the ground immediately behind the paw, without interfering with the dog's normal position/stance. Whether in the GSD, Vizsla, wolf, Saluki, or most ancestral-type breeds, these proportions suit the function of versatile hunters, herders, and other utilitarian dogs.

There is a small discrepancy between definitions of withers and where in the withers to make the height measurement. The AKC has chosen to rest the wicket on the highest point of the shoulder blades, and in large, steep-shouldered dogs, that can easily be an inch or 3 centimeters higher than the distance as measured the European way. It can make a noticeable difference in visual impression, however.

The measurement in the (2003) current or proposed Vizsla “proportions controversy” does not address a minor problem as well as the SV Standard does. In the Vizsla, “the elbow” is not defined as a specific point of reference. That is, where is “the elbow”? At the center of the humeral condyles? At the bottom, where the joint gives way to the radius and ulna? At the top of the olecranon process? (That last point is the best place because it is visible and definite, and is generally assumed by Vizsla people to be where the term refers to.) A better description of where the judge's eye and/or hand should be drawn is in the (German) GSD Standard: the underline of the chest between and immediately behind the elbow. Problems arise when you get dogs like the Alsatian and some of the deep-chested GSDs in American lines, where the point of the elbow is noticeably higher than the bottom of the sternum, while other shallow-chested dogs have the underline noticeably above the elbow. In any breed, these differences should be accounted for. In most breeds, they will be very close to the same distance from the ground. There is no significant variation between evaluators if that is used as the dividing line between top and bottom “halves” of the dog's outline and height. In most medium-size and ancestral-type breeds, the distance below the underline of the chest will be practically the same as for the distance from point of elbow to ground. That is, the top of the elbow's olecranon process with be very close to being in the same plane as the part of the sternum between the legs. By the way, when I speak of leg length here, I mean to draw more attention to the lower leg, even though the upper arm will also be longer in moderately or very tall dogs.

Sighthounds are typically built with even a greater leg-length-to height ratio than the gundog, guardian, and herding breeds. Their more upright shoulders and croups serve them better for the double-suspension gallop in which they “fold up” and extend to a greater amount than other breeds do, and the more vertical foreassembly results in a little more space between the olecranon and the underline. The shorter the breed and the dog, the lower will be the leg-length-to-height ratio. Think of most Toys, Cockers and Corgis, but also Brittanys and smaller dogs.

There are good, function-related reasons why history has given us these ratios. Breed Standards ideally are written to describe the breed as existing at the time; i.e., the best, most functional, most useful specimens. If (that might be a BIG “if”) the breed is represented by a population that does its job well, whether endurance trotting during herd control, or bounding over obstacles and broken-field running after game, etc., and if the Standard writers are knowledgeable about anatomy, the Standard might be written well. There are some that are abominable for one reason or another, and there are some (such as the SV's) that are excellent, though not faultless. Complexity is not always beneficial — the Greyhound Standard is the soul of brevity, yet the breed has not suffered greatly from the artificiality of dog show guidelines for breeding. The re-writing of the UKC Standard for the American Pit Bull Terrier greatly increased its length, but did nothing at all to change experienced breeders' and judges' mental image of the ideal in that breed. The biggest reasons for some Standards not rising to the good sense and usefulness include changes that originate from club members' fancies more than in the dogs' function. The best that a dog show judge or breeder can keep in mind is, “Does this dog look like it can do the job for which the breed was developed?” And, “Does this dog look enough like all the other good examples of its breed?”

Quoting from a document circulated by Vizsla Club of America members, “It should be noted that the change originally proposed by the VCA's Board of Directors has been amended by the addition of the following proposed sentence: ‘Under no circumstance should the distance from the elbow to the ground be less than the distance from the elbow to the top of the withers.' While this eliminates one of the concerns raised with respect to the original proposal, the essential objection remains that this proposal would allow a functionally incorrect dog that is too low on leg to be described as ideal.” It is obvious that opponents to the Standard change are afraid of letting the camel get his nose into the tent.

Now, there will not be any substantial damage to the Vizsla if the American club decides to call for a 50/50 ratio in height. But if you go in that direction, there will be many more cases of dogs with actually shorter legs than proscribed, and many of them will be awarded championships by judges who do not care enough about function, history, or club preferences. Look at what has happened to the American-lines GSD. Besides an extreme variation in type that is being rewarded with show wins, there is a big problem with far too many being too short on leg. In some cases, the observer is almost reminded of Basset Hounds. I believe much of that slide into incorrect proportions comes from an unfortunate misapplication of the concept of American independence, and a haughty, superior attitude toward the country-of-origin. In most cases, the originating country will have produced the more correct dog, and the reason for that is simple: it is there that function had formed the breed. In the cases of both the GSD and the Vizsla, and I daresay most other normal ancestral-type breeds, the leg-length ratio in the original examples (and hopefully in the written Standard) will be similar to that of the German GSD: approximately 55% of height below the underline at the elbow area.

Wording is important in any written Standard and in communications to club members and judges. The arguments regarding the VCA Standard unfortunately lack a little clarity in definitions. In the same paragraph in one very good document circulated among VCA members, the “Depth of Chest refers to the distance from the top of the withers to the elbow, the chest being understood to come down to the elbow as called for in the breed standard. Length of Leg refers to the distance from the elbow to the ground.” and, “…measuring the length of leg below the chest and dividing it by the depth of chest. Assuming the keel of the chest to be level with the elbow, this ratio can also be expressed as a measure of the distance from elbow to ground divided by the distance from top of withers to elbow.” As I indicated, since the composite picture of all the bones in the elbow of dogs of this size can be as much as 3 inches in its own depth, that quote does not give us precision. However, I have been assured by a trustworthy source in VCA that they indeed mean a reference point , not a reference area . Further VCA discussions should state that all parties are settled on such definitions before continuing, I think. Saying that the chest should ‘come down to the elbow” is probably better stated that “the keel of the chest” is level with a specific, anatomically-identifiable part of the elbow, the top of the olecranon process, also called the point of the elbow. It should be spelled out in plain language.

It has become customary in some registries for judges to appear to treat all breeds as having the same historical function. That is, they incorrectly give as much emphasis to outreaching gait in a Shiba, Italian Greyhound, or terrier as they do to a sheepherding breed whose ancestors' job required endurance trotting. An APBT/AmStaff, a Chow Chow, or any of the Bulldogs and mastinos/molossers were not modified for sheep herding and tending, but for fighting, and therefore the ability to get its feet under itself with strength and stability was more important than length of lower forearms or lower thighs (the latter popularly known as “rear angulation”). Otherwise the boar or bull would make short shrift of them.

Most hunting breeds of greater height than the Beagle have an intermediate function and structure between the terrier-schnauzer-pinscher types, the sheepdogs, and the sighthounds. They are not required to be as angulated in the rear as the all-day trotter, nor to be able to turn on as small a dime as the Shiba, nor have the low, square stance that keeps the fighting-breed dog from being rolled over. Neither should they depart much from the chest depth to overall height ratios as required by the Standard for the very utilitarian and versatile GSD.

Yes, it is important to have accurate measurements if one is to keep the breed in question to its original or revised function description. One means of insuring that is to explicitly and unequivocally define terms and reference points, and one means of enforcing that is the breed survey. Periodically or else in the case of every dog passed for breeding rights, the dogs in almost every breed should be measured and the results recorded, later to be compared with performance results, taking into account the variable effect of attitude and “drive” as well. The SV requires each individual to have a performance title (such as a schutzhund degree) and other prerequisites, and to be thoroughly “measured in” before eligibility to breed, or allowing any of its progeny to be registered as purebred. The Germans are great for keeping meticulous records, and breed surveys for such dogs as the GSD, Rottweiler, and many more are very valuable to the conscientious breeder. Those who do the measuring and certifying must pass rigorous tests as well. Once the dogs are admitted into that surveyed group, the judge can use visual comparison to segregate them according to more minor individual differences.

There exists the myth that “increasing the length of leg invariably results in a poorly angulated front.” Perhaps this misconception comes from the observation of sighthounds, who as a rule have concurrently both a relatively upright front and more space than other breeds between the chest underline and the “point of the elbow” (top of the olecranon). Those who have been fooled by this have perhaps not looked at the all-too-common, short-on-leg American GSD whose notoriously vertical foreassembly makes the legs appear to have been dropped from the ears with the help of a plumb line. The fact that many of the taller dogs, the ones with longer lower legs and the chest obviously above the point of the elbow, are sighthounds and thus more vertically constructed in front, is coincidental. Other breed types that include tall dogs have no such effect of size or height on front angulation.

Getting back to the gundog, and specifically the [golden/russet(?)-colored] (fanciers hate the accurate scientific term “liver-colored”) Hungarian: Cliff Boggs, the author of The Vizsla said “the length of the front legs from the elbow [the top of the olecranon] should be about equal to the depth of the body (chest) at that point.” Actual measurements made by that author gave “legginess ratios” ranging from 1.23 to 1.04 while not a single one of the dogs measured by the book's author had 50/50 proportions. Boggs clarified the statement, saying, “…the legs were longer than the depth of the chest, which represents better proportioned Vizslas. If I had to choose a ratio it would probably be 1:1.14 ….I would not do it without adequate statistics. It is just my opinion from forty-plus years of breeding, training and competing with the breed.”

There is nothing like actual, accurate measurements, something the Germans in the SV and elsewhere have been famous for. Many of their statistics over a century are mentioned in my book (The Total German Shepherd Dog), the seminal book by Max von Stephanitz, and records in SV archives. The meticulous observer Curtis Brown said, “Although …longer-legged sporting dogs should be able to trot well for their build, in the field they are designed more for galloping than for trotting.” In this respect, most of the pointer, setter, and retriever breeds are intermediate between the tending/herding-specialist type like the GSD and the purely galloping breeds such as the Greyhound. Even the GSD with its modern job utility has more function in agile galloping and jumping than it had when it was selected from the tending dog that moved flocks from pasture to pasture, and watched out for predators.

Another matter of proportions that is being bandied about in the current controversy is that of humerus (upper arm) to scapula (shoulder blade). It is a common mistake for people to latch onto drawings from the 1890-1920 era, some of which predated radiographs. But still, these early fanciful artists had fingers, and obviously did not use them. The proportions and the locations of bones and joints are grossly misrepresented. Yet, here we are in the latter days of “the age of enlightenment”, with most people still believing those erroneous claims of how a dog is constructed inside! There are minor differences from one dog to the next, in lengths and ratios of scapula to upper arm, but as little as a centimeter can show up in the appearance in stance and movement, since each bone is only a relatively few inches long. In the herding dog more than in the terrier-pinscher type, an upper arm as long as possible is of great benefit. It gives more room for muscle attachment and therefore promotes endurance as well as length of stride, springiness for jumping, and cushioning for landing. Naturally, such benefits are also desirable in a hunting dog such as the Vizsla.

I think everyone, whether he relies only on archaic pictures or on fingers and field experience, will agree that the ideal foreassembly has a scapula and upper arm of approximately the same length, and that restriction of trottin g movement and efficiency results when the humerus is shorter, or when the angle between the two is extremely open. But one problem in describing or seeing the best shoulder is the inability to see radiographically, as Superman could in the comic books. Where the joint is, what the angle is, and where to draw the lines, even on a radiograph, are things not understood or agreed on by all. Even feeling the joint, or flexing the shoulder and arm to estimate the lengths, do not result in accurate measurements. Something like Rachel Page Elliott's fluoroscopic moving pictures are needed. Or at least, successive radiographs of the front assembly of a dog in various degrees of flexion. The old sketches, often lifted from the 1920s book by von Stephanitz, the founder of the GSD breed, are very misleading regarding location and shape of bones, and location of the rotational axis in the joint. What you feel with fingers and see on the line drawing is not the center of that rotation! In my book, The Total German Shepherd Dog (www.hoflin.com), there is much more in the way of correct illustration and outlines of actual radiographs, and at least 17 of the 20 chapters are applicable to all breeds. Highly recommended.

I have already said that the bones involved are not very long, and that a small change in length or ratio can have a noticeable effect on gait. Another thing to learn is that, while there are variations from one breed to another, and even within a breed between individuals, these variations are far less as you approach the midline and spinal column. That is, scapulas of different dogs are closer to being identical in length and layback (angle or slope) than is the case with the upper arms. There are more variations in lower leg length and shape between breeds than there are in the upper arm. Likewise, the range of motion increases tremendously as one goes from spinal column to end of limbs. Judges and breeders need to focus on the upper arm far, far more than on the scapula; in fact, we could just as well forget about the scapula altogether in most examples, and get along with our breeding programs just as well. Of course, there are going to be extreme examples, but these very upright shoulder blades will not be hard to spot. Such dogs, though, are likely to have concomitant short and vertical upper arms. The combination makes the situation worse, but the major contribution to a “straight front” (as seen from the side) is in the upper arm.

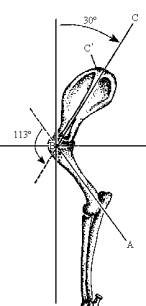

It must be remembered, when looking at some artists' fanciful concepts of skeletal structure, that the 45-degree laybacks of upper arm and/or scapula are purely myths, promulgated by drawings that are not based on radiographs or even finger palpation. In my anatomy-and-gait seminars, I draw chalk lines on volunteered dogs, and have the audience feel where the articulation is, and what the layback angles actually are. You cannot remain blind when you experience this. Figure GSD-1 is an accurate representation of the proportions of a very good shoulder, drawn from a radiograph of a standing dog of excellent structure.

Fig. GSD-1 An ideal GSD shoulder,

drawn live from standing radiograph.

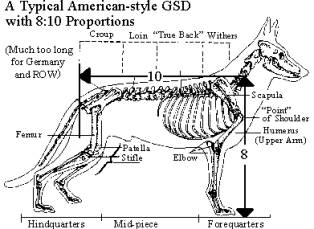

Fig. GSD-2 Measured from top of blade, AKC-style, half of

this dog's height is to the point of the elbow. Many American

GSDs have deeper chests and shorter legs, so even an 8½ : 10

dog looks too short on leg. Now measure European-style, from

just behind the top of the blade, their definition of withers.

Another very important matter of proportion is height-to-length. We shall leave out the poorly-worded and incorrect descriptions such as found in the standards of the Jack Russell breed and others, and look instead at the two breeds mainly discussed above. In a work presented by Vizsla and German Shorthaired Pointer fancier François Bernier of Hull, Quebec, on the website <www.bajnok.com>, some excellent illustrations indicate that the best Vizsla or GSP length-to-height ratio is approximately 1.09 (0.91 height-to-length), in other words, about 9 high to 10 long. It may surprise AKC-show-goers in the U.S. that this is close to the ideal for the GSD according to its country of origin, as well. That's because more American-lines GSDs are closer to an 8-to-10 ratio, with a longer, lower look than the international dog has. The SV (WUSV and FCI) Standard for the German Shepherd Dog says, “The length of torso exceeds the measure of the withers height by about 10 - 17 %.” That translates to between an 8.5-to-10 and a 9-to-10 ratio of height to length. The GSDCA wants a longer dog, that is between 8-to-10 and 8.5-to-10, something I opposed when I was on the Board of Directors and afterwards. So the typical AKC dog is usually at one extreme (8:10) and the typical gundog is at the other extreme of this length/squareness range, 9:10 and the international GSD is in between, and a little closer to the working ideal of the pointing breeds. Figure GSD-2 shows a typical American-style GSD with proportions that are not acceptable in the rest of the world (except part of Canada and a couple of pockets here and there amid the internationally-accepted dog in other countries). What I am saying is that the typical “AKC Shepherd” does not look much like the breed as recognized in the rest of the world.

The Breed Standard of the SV (Parent Club for GSDs, HQ'd in Germany) says: “The depth of chest should be about 45% to 48% of the dog's height at the withers. The ribs should widen out and curve moderately.” This Standard is accepted by almost every country in the world, the U.S.'s AKC club (GSDCA) being a flagrant exception. You can find my translation of the Standard, the best in the English language, on the <http://realgsd.info> and other websites.

Background

In 2001, several Vizsla fanciers rose in opposition to a proposed change in their breed standard that would describe the distance from the elbow to the ground as "approximately equal to the distance from the elbow to the top of the withers." It was the opposition's view that their breed historically had and functionally needed a length of lower leg greater than the distance from the elbow to the top of the withers. They succeeded to some extent by persuading the VCA Board to amend the wording by adding, "Under no circumstance should the distance from the elbow to the ground be less than the distance from the elbow to the top of the withers." The dissenters still felt that this amended proposal would allow a functionally incorrect dog, too low on leg, to be described as fitting within the definition of “ideal”.

Francois Bernier, and the large number he was spokesman for, continued to believe that the most correct dog should have a lower leg longer than half the dog's height at the withers.

This group agreed on certain definitions of terms such as depth of chest, to be the distance from the top of the withers to the elbow, as long as the chest was understood to come down to the elbow, as called for in the Standard. Height was defined as the distance from the top of the withers to the ground, although they did not adequately define “withers”.

A “legginess ratio” (LR) was to be determined by measuring the length of leg below the chest and dividing it by the depth of chest. Presumably that would be close to half the height of the typical dog, assuming the chest underline to be on the same level as the top of the elbow. Thus, the LR can also be the distance from elbow to ground divided by the distance from top of withers to elbow. The greater the legginess ratio, the greater the denominator (the longer the leg length in relation to the dog's height. A ratio of 1:1 shows a leg length equal to half the height, while a ratio of 1:1.2 denotes a dog with a leg length that is 55% of total height. This latter figure is another way of stating what the GSD Standard does in different words.

Importance of Accurate Measurements

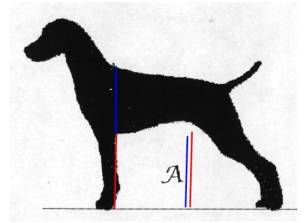

For the sake of accurate compilation of data such as is needed in a breed survey system, and for training one's eye, visual assessment should be compared with actual measurements whenever feasible and possible. The silhouette of the Vizslas in Figure Vizsla-1 was distributed with a statement that it was “equidistant, withers to elbow and elbow to ground”. However, it was measured (on the photographs) and found to properly have a length of leg greater than half its height . I have long seen that optical illusions are common in the view of dog's proportions. The dogs with measured leg length equal to chest depth almost invariably look low on leg. Part of this comes from the fact that more than half the Standards and indeed more than half the breeds, are slightly longer from breastbone to buttocks than they are tall (to either top of scapula or to the withers behind the blade, where the wicket would rest on a vertebra).

Figure Vizsla-1 : The shorter line under the silhouette is

the depth of chest and the longer line is the length of leg.

Since the arguments in the Vizsla camps centered on whether or not an ideal Vizsla can in fact be “equidistant withers to elbow and elbow to ground”, Bernier found it surprising to find the VCA-proposed change to be illustrated with silhouettes of dogs whose leg length was in fact greater than half the height. Perhaps someone was falling into the old error of making a statement without backing it up with scientific evidence. I have been preaching and teaching for decades about the erroneous skeletal angles reported by so many books and authors who have copied from each other for 100 years instead of taking radiographs and measurements on the actual dog, so I know firsthand the frustration in the Vizsla world. One of the problems with the VCA proposals is that the proponents of the initial proposals lost additional credibility by using drawings that purported to show extremely short upper arms, and that further, they were related to greater LR, yet which (drawings or statements) were not based on radiographs or anything other than wild imagination. The expose can be found in detail on the website, <http://www.bajnok.com/vca.htm> and in my book on the GSD as well as magazine and website articles. I have based my statements on actual, living dogs, radiographed while standing naturally; these observations have been backed up by like-minded authorities who believe in measuring and checking hypotheses, such as Rachel Page Elliott and Curtis Brown. But front angulation is a different subject, covered elsewhere. I only bring it up here because the VCA has made the same mistakes regarding that subject as well, as so many other writers and clubs have.

In speaking about the purpose of the Vizsla in relation to the leg length and height proportions; Bernier reminds his fellow fanciers that “Any discussion of the desirable proportions of a Vizsla must take into account the purpose of the Vizsla as a utility hunting dog. The gold standard of conformation is that which will allow the Vizsla to fulfill this purpose the most efficiently. The purpose of the Vizsla is NOT to go down-and-back and around in a show ring at the trot. All available experts concur that the optimum conformation for a dog whose primary working gait is the gallop involves a length of leg greater than half the height. I have yet to see those who wish to argue that a LR of 1:1 is optimal for a hunting dog reference any expert evidence in support of their view. A great many of the herding breed Standards call for a LR ratio of 1:1. The primary working gait of the Vizsla, on the other hand, is the gallop, and it [is] expected to ‘hunt with endurance at moderate galloping speeds'”, Bernier says. He quotes Curtis Brown as saying, "Although these breeds [longer-legged sporting dogs] should be able to trot well for their build, in the field they are designed more for sustained galloping than for trotting."

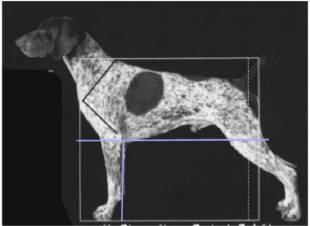

Taking a look at a GSP with a LR Nearly 1:1 and a Vizsla that “has” a 1:1 ratio

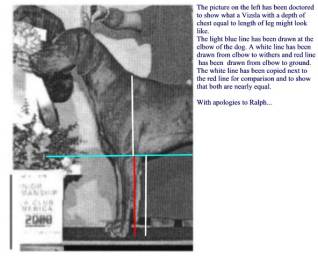

Just for the fun of it, Bernier illustrated (Figure GSP-1) a picture of a German Shorthaired Pointer he used as a stud. “This is a superb dog that was a Top Ten GSP for three years running, has won numerous breed specialties, was awarded two BIS wins, and has produced over 60 champions. His fault: he lacks a little leg under him. This dog almost has --but not quite-- a legginess ratio of 1:1 (something that is made worse in his case because the chest practically drops below the elbow). [Compare him with] a doctored picture showing what a Vizsla might look like (Figure Vizsla-2) [that has] a length of leg equal to half its height at withers. Is this hypothetical Vizsla a breed ideal? Or even close to it? The 50/50 proportions, besides the fact they are functionally incorrect, result in a dog that has a cloddy appearance and is completely devoid of elegance.”

Figure GSP-1:

Figure Vizsla-2. Figures compliments Francois Bernier

Bernier brought up a possible health concern raised by Stephanie Russo, DVM: If the breed standard were changed to indicate that a Vizsla with a legginess ratio of 1:1, or nearly so, represents the "ideal", one would expect that in time, breeders would seek those proportions. Given that Vizslas do not generally exhibit such a ratio at the present time, achieving a legginess ratio of 1:1 would involve breeding for a decreased length of leg and an increasing depth of chest. Russo warns that such a change in conformation might put the Vizsla at increased risk for gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV or “bloat”). She wrote: "I can assure you that Weimaraners and Dobermans are very prone, and it's curious that they are both breeds listed as having 50:50 proportions. I think that perhaps historically only the large breed dogs have had really deep chests – [most of] the medium sized dogs have not had such deep chests. If the Vizsla chest is intentionally made deeper I really believe that the deep chest will put it at risk. This would be a major mistake."

In cursorial animals, increase in speed, which for a hunting dog means covering more ground in less time, is achieved by lengthening of the legs. This applies equally in dogs where increase of leg length across various breeds is commensurate with specialization for galloping. Only the British Vizsla standard and the breed standards of the Weimaraner and Brittany support the view that leg length is half the height. The current FCI/Hungarian standard explicitly confirms that leg length is greater than half the height at withers. Drawings that have been claimed to represent Vizslas with a leg length equal to chest depth actually show dogs with a leg that is longer than half their height. This indicates a need for the use of actual measurements instead of visual estimates by those using those illustrations. The author of The Vizsla (2nd edition) acknowledges that the "better proportioned Vizsla" will have a length-of-leg greater than half its height.

Other points of discussion regarding body proportions among Vizsla fanciers include height to length of torso ratio. The extent to which a Vizsla is longer than tall is about 4% to 6% of its height. Vizslas that significantly exceed this range may appear low on leg, even with a proper chest-depth/leg-length ratio. The extent to which the leg is greater than the height may range from 6% to 10%. One way around the arguments would be say that “The distance from the elbow to the ground is slightly greater than half the height at the withers." If the height of the leg is measured relative to half the height of the dog rather than relative to the depth of chest, the difference between the two represents a percentage that is more comparable to that of the length/height difference. For example, on a 24" dog that has a legginess ration of 1:1.2, leg length will exceed depth of chest by 2" but will only exceed half the height at withers by 1". The difference between length of leg and half the height at withers would range approximately from 3% to 5%. This would justify using the same word "slightly" in both portions of the standard.

References

Fred Lanting, The Total German Shepherd Dog , 1999 www.Hoflin.com

Curtis Brown, Dog Locomotion and Gait Analysis, 1986

Edward Gilbert & Thelma Brown, K-9 Structure & Terminology, 1995

Leon Hollenbeck, The Dynamics of Canine Gait , 2nd edition (1981)

Rachel Page Elliott, The New Dogsteps (1983)

Harold R. Spira, Canine Terminology (1982)

Frank Jackson, Dictionary of Canine Terms (1995)

Robert Cole, You Be The Judge: The Vizsla, Dog News, March 12, 1999

Milton Hildebrand, Analysis of Vertebrate Structure, 4th edition (1995)

A. Brazier Howell, Speed in Animals , (1944)

Fran çois-R. Bernier (Hull, Quebec), et al., Submission to the Officers and Board of Directors of the Vizsla Club of America Concerning Proposed Breed Standard Changes , (2001)

Articles by international judge and teacher of anatomy, Fred Lanting, on various websites.

Various breed specific books and articles have also been consulted.

************************************************

Ed. note: Fred Lanting is a lecturer in anatomy and gait analysis, who has been breeding since 1945 and who got his first German Shepherd Dog in 1947. He has handled all breeds in the U.S., Canada, and other countries, but mainly GSDs, sighthounds, and sporting breeds. He leads tours each September to Germany's largest specialty breed show, with sightseeing as well. E-mail him at Mr.GSD@Juno.com or mrgsd@hiwaay.net for permission to reproduce this.

************************************************

copyright, Fred Lanting. mrgsd@hiwaay.net

Consider joining my Sieger Show tour each fall — see Germany and other countries, visit training clubs, meet breeders, and get a judge's perspective on the world's biggest specialty dog show.